The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open directed and written by Elle-Maija Tailfeathers and Kathleen Hepburn follows two indigenous women in Canada and their physical and mental journey throughout a single day. Áila and Rosie meet in an unexpected way; Áila is coming home from her doctor’s appointment – where she had just gotten an IUD – and Rosie had just ran out of her apartment, heavily pregnant and barefoot, where her boyfriend had started beating her. Áila rushes Rosie to her home, and their journey begins.

The two women are complete foils of each other, despite that they are both from similar indigenous backgrounds. Áila is a 31 year-old woman who seems to have her life together; she lives in a nice house, has a steady relationship, and has no plans of having a baby. On the other hand, Rosie is 19 years old and is very pregnant, lives in a small apartment that is actually her boyfriend’s mom’s, and is in an unsteady and abusive relationship. Their personalities differ too; Áila is more gentle, caring and soft spoken, whereas Roise has quite the mouth and fiery personality when she’s not silent. Another important difference is that Áila has lighter skin, and Rosie has darker skin. This foil creates an interesting and important dynamic for the film.

Something that caught my attention during the film was that the view of the women in some shots was partially obstructed, and most notably, by a wall or the edge of a wall or door frame. This technique I believe not only reflects the viewer’s position, but the two women’s as well within that scene.

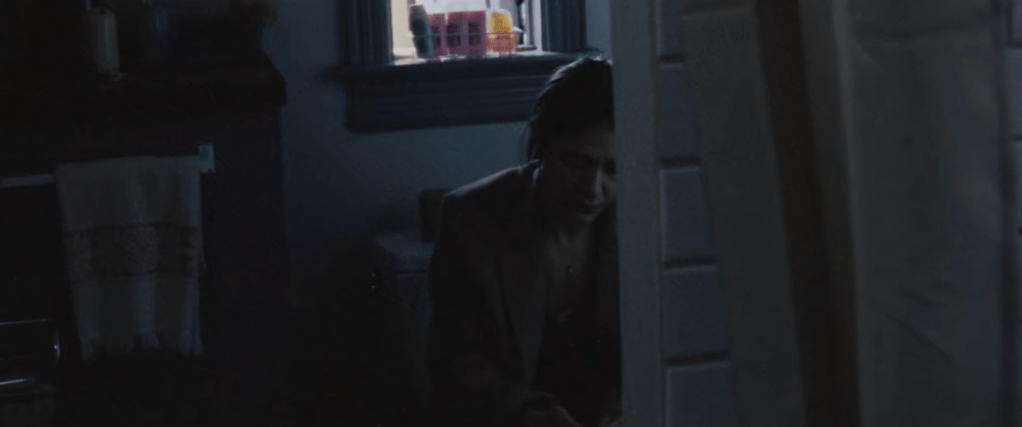

Towards the beginning, after Áila has taken Rosie into her home, Áila goes into her room to try to find some clothes for Rosie since she is soaking from the rain. She rummages through her partner’s clothes visibly upset and distraught, and you can hear her heavy, shaky breathing. This scene is shot from a side angle behind her, where the edge of the doorway is obstructing the shot. After picking out a pair of pants and a shirt, she sits down on the bed and looks at herself in the mirror, then tries to calm down. Here, We see Áila’s face through the mirror, and not directly. The shot is still obstructed by the edge of the doorway (00:17:42-19).

Here, the obstructed shot visibly reflects how Áila’s life in this moment is being obstructed by Rosie’s dire situation. She is distraught and upset, no longer as calm as she had been portrayed as up until this moment. This technique also reflects how Áila is hiding her emotions from Rosie; she is hiding behind a wall, then calms herself before she goes to the other side. I think that this shows a lot about how kind Áila is, and ironically, how motherly she is as well. Parents, including mothers, don’t want to show that they’re sad or stressed in a dire situation so that their kids can stay positive. In a way, Áila is doing that here. Additionally, by using the edge of a doorway, in this moment it can be seen as her entry into this journey of helping Rosie. Not only can she be calming down in this moment, but preparing to enter that doorway, that journey, where she can’t come back from. By having the edge of the doorway hover within the shot, it almost reflects how much the choice of whether helping Rosie or not is weighing on her mind as she gets clothes for her.

After Rosie has changed into the new clothes, her and Áila sit in a small living room space and begin to have a conversation. This medium long shot, which shows the back of Áila and Rosie facing her, also has an obstructed view, with the edge of a wall on the left side being in it (00:28:42-32:50). During the beginning of the conversation, Áila tries to get Rosie to open up about herself and her life to try to help her. She asks if anyone is looking out for her, and what she wants to do. Rosie gets defensive and skeptical, and continues to dodge her questions.

The obstructed shot here with the edge of the wall parallels the wall between Rosie and Áila not only in this scene, but their lives in general; their foil. Rosie also puts up a wall so that Áila may not enter her thoughts, feelings, or life. We see this wall with her refusing to answer personal questions and being very skeptical of Áila and her motives of helping her. In fact, the wall becomes more apparent when it seems to start coming down (metaphorically and physically). After a while, Rosie tells Áila that she has bled through her pants; she then goes to change, and when she comes back, the shot is not longer filmed with the wall obstructing the frame. In fact, after Áila comes back, Rosie starts to become less reluctant and open up to her older counterpart by answering some questions. Here, the wall is physically out of the shot, which parallels how Rosie has started to take her own down.

In terms of subjects for this film, or marginalized indigenous women, I believe that this technique connects with them in a way that it shows respect for them. The obstructed shot gives the women privacy in other moments, such as when Áila is using the restroom in the safe house towards the end of the movie. This prevents the movie from objectifying her body by not showing it through a male gaze. In the shots mentioned above, it also reminds the viewer where their place is within this story: as an observer. I think this gives the subjects some respect in the way that it reminds the viewers that they’re observing something that is real; something that actually happens, and needs to be recognized. But, we can no longer be the observer; we must take action. This shot almost criticizes the world, and audience, for just being an observer of marginalized women and their struggles, and hiding behind a wall pretending like we can’t see it.

The authorship of this film is also very unique. Although I have not seen any of the other films of the two directors, I believe if they closely follow the film style of this one, they could be considered “film auteurs.” In Film Feminisms: A Global Introduction, Kristen Lené Hole and Dijana Jelača write that “Auteur Theory particularly privileges those directors who are seen as shaping movies according to their unique aesthetic vision and worldview, rather than ‘merely’ restaging existing paradigms of film language” (Hole and Jelača 7). Not only do these obstructed views contribute to the film’s aesthetic, but other shots as well. The camera parallels the walking and movement of the characters for almost the entire time, mimicking their bobbing of the head, walks, shaking runs, and frantic movements. For me, at least, this was something that I thought was very unique to these directors; while this camera technique is used in some specific scenes in other films, it isn’t used for the majority of the time like in this one. Their worldview as well is significantly particular and different from most other film makers, as they focus on marginalized indigenous women in Canada, and one seemingly small day to reflect societal culture’s ostracization, internal problems, and treatment of indigenous women as a whole. The overall theme of the movie as well as the filming style creates an overall personality for the directors, I think.

Works Cited

The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open. Directed by Elle-Maija Tailfeathers and Kathleen Hepburn, performances by Violet Nelson, Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers, Charlie Hannah, and Barbara Eve Harris, Experimental Forest Films, 2019.

“Chapter 1: Women Filmmakers and Feminist Authorship.” Film Feminisms: a Global Introduction, by Hole Kristin Lené and Jelača Dijana, Routledge, 2019, p. 7.

One reply on “Obstructed Views”

Love your discussion of the obstructed views, and agree with your points about the important differences between the two women. There is one way, however, in which they are not that different. You say that Aila “seems to have her life together,” and I think that “seems” is the operative word here, and points to one way that the two woman are not that different (i.e, the both don’t have their lives “together”). Even though Aila seems to wants to present herself as having her life together, when she’s alone we see her crying several times in the film, and even the IUD scene suggests that she’s having some struggles. I don’t think the film makes the nature of these struggles clear (are they related to her decision not to have a baby at this point?), but Rosie is certainly onto Aila, and knows that Aila isn’t as put together as she presents herself. Rosie is, in some ways, more perceptive than Aila, don’t you think?

LikeLike