Warning: this review contains spoilers.

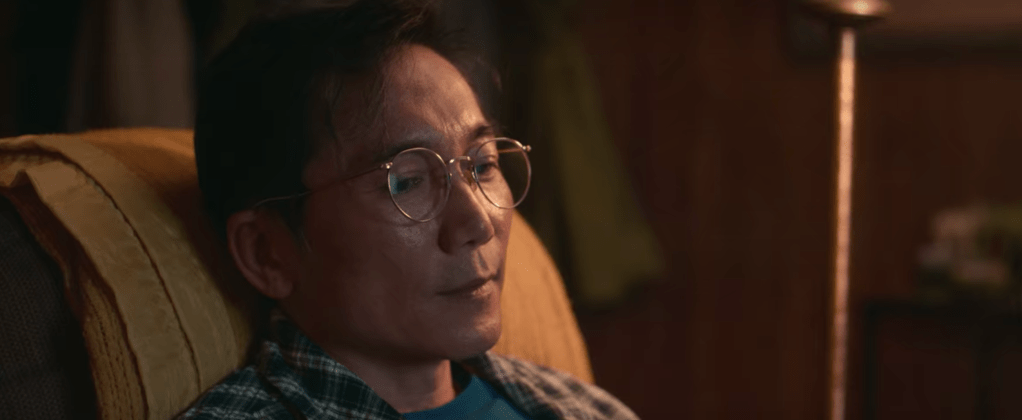

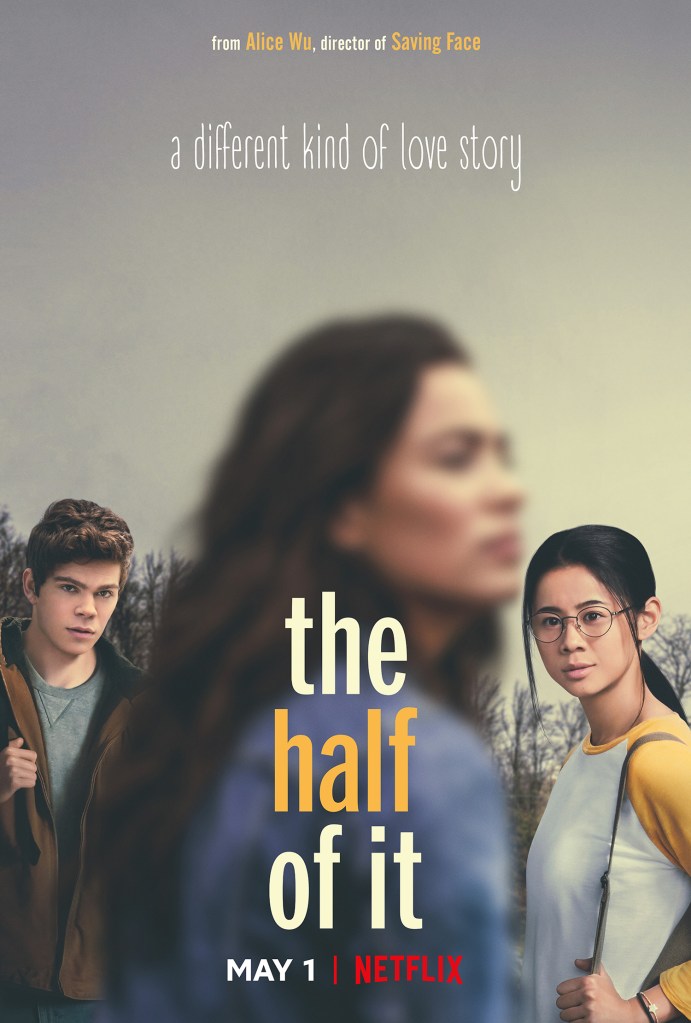

The Half Of It directed and written by Chinese-American, lesbian Alice Wu was recently released by Netflix on May 1, 2020. The film follows witty Ellie Chu, a Chinese American immigrant living her life in a small town called Squahamish with her widowed father, as she helps Paul Munsky (who is usually called Munsky), a shy jock, write letters to his crush Aster Flores. Little does Munsky know – but the audience is clearly aware – that Ellie also has a crush on Aster. Through this seemingly typical love triangle (spoiler: it’s not), the audience explores Ellie’s struggles with class, racism, love, friendship, and blossoming sexuality. In this blog post, I will be explaining why The Half Of It is a much needed film in today’s society because of its inclusivity and intersectionality of class, gender, race and sexual orientation, as well as subversiveness to patriarchal and Hollywood norms and expectations.

If you would like to read a more detailed summary of the film click here. And yes, I know it’s wikipedia, but they had the best detailed summary I could find.

THE BECHDEL TEST

The Half Of It passes the Bechdel Test, which originated from a comic strip called “The Rule” created by Alison Bechdel (who credits it to her friend Liz Wallace). It is used to examine the presence and representation of women in a film. To pass this test, the film must have the following:

1. The movie has to have at least two women in it,

2. who talk to each other,

3. about something other than a man.

Some have even added that the women have to have names as well. Despite that a lot of Ellie’s interactions are with Munsky and her father, her conversations with Aster, her female teacher and somewhat mentor Mrs. Geselschap, and girls at a party have to do with something other than a man. Even though Aster and Ellie’s most prominent bonding moment did have Aster talk about her love life with Trig, it wasn’t the only thing they talked about, and most notably it was not the subject that started or ended that scene.

Now, not every movie that passes the Bechdel Test can be considered “feminist” or a very good representation or women; for example, Fifty Shades of Grey passes, yet over-sexualizes women and promotes abusive relationships. In any case, I would at least consider the Bechdel Test to be a “jumping off point” for good female representation in films. For The Half Of It, passing the Bechdel test shows the significant presence of not only one female character, but two (Ellie and Aster), and makes the female characters have depth beyond their concern for boys, which many teen movies fail to do. It also allows the movie to live up to the lesbian representation in the film: if Ellie had only talked about guys with another girl, it would have possibly sabotaged her portrayal by diminishing her presence as not only a female character, but as a lesbian.

Even though we are in a progressing society, many films fail to pass the Bechdel Test and fail to provide realistic, non-patriarchal performative female representations. But, The Half Of It does; girls and women alike don’t always just talk about guys, and even though this is a film about love, it’s important to show that guys or other love interests don’t define a woman’s character or life.

THE VITO RUSSO TEST

This film also passes the Vito Russo Test, which was inspired by the Bechdel Test. The Vito Russo Test, created by GLAAD, an organization that actively counters LGBTQ+ discrimination in the media, was named after a LGBTQ+ film historian, author and activist Vito Russo. It is used to examine the presence and representation of LGBTQ+ characters in a film. It has 3 criteria to meet in order to pass:

“ The film contains a character that is identifiably lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and/or queer.

That character must not be solely or predominantly defined by their sexual orientation or gender identity (i.e. they are comprised of the same sort of unique character traits commonly used to differentiate straight/non-transgender characters from one another).

The LGBTQ character must be tied into the plot in such a way that their removal would have a significant effect, meaning they are not there to simply provide colorful commentary, paint urban authenticity, or (perhaps most commonly) set up a punchline. The character must matter. ”

GLAAD

This test’s criteria is a little more specific than the Bechdel Test, but this helps to ensure that there is non-detrimental and more accurate representation and portrayls of an LGBTQ+ character.

For the first part, Ellie is our character who is identifiably lesbian. Of course, every summary of the film mentions her love interest, Aster, or directly references her sexuality. However, if you were to watch the film without having any previous knowledge of it, the audience figures out Ellie’s interest in girls within the first 11 minutes of the movie. First, after Ellie’s voiceover of a greek myth about finding our “other half,” we see her looking at Aster as she sings in music class, the voiceover saying

“In case you haven’t guessed, this is not a love story. Or, not one where anyone gets what they want.”

(Wu 6:00)

Five minutes later, Ellie is helped out by Aster when someone bumps into her and knocks over her stuff in the hallways of school. Ellie, obviously love struck, manages to blurt out “I’m Ellie Chu” (Wu 10:25). Her feelings towards Aster become even more apparent in this scene, and continue to develop throughout the rest of the movie.

Ellie is also not solely or predominantly defined by her sexuality. Ellie is a great writer, witty, a beautiful singer, intelligent, funny, a great friend to Munsky, hard-working, loving daughter, caring, Chinese-American, and more. This is not a coming out movie, technically, which is another great aspect that helps alleviate her from being defined by her sexuality. While her sexual orientation plays a big part of the plot in the movie, it does not play Ellie’s whole character.

Lastly, if Ellie were removed from the film, there would be no film. Ellie is the center, as this story mainly revolves around her, and how she impacts the lives of others around her. To be more literal, if there’s no Ellie, there are no beautifully written letters for Munsky to give to Aster, and thus even if the script were to only include Munsky trying to win Aster over on his own, he would fail – end of story, end of film.

Passing the Vito Russo Test ensures that Ellie, our LGTBQ+ character, isn’t just in the story for representation’s sake, or as a joke, or a one-dimensional character, which subverses much of Hollywood’s representation of the queer community. Ellie is such a dynamic character who has many struggles that she is going through in life; a lot of people don’t have the luxury of just focusing on one, which is what a lot of films tend to do, especially ones with characters coming out as LGBTQ+ – Hollywood and the rest of the film industry needs to start moving on from coming out stories of teenagers. The Half Of It is a true inclusive film of a character who is LGBTQ+, which is something that is desperately needed.

INTERSECTIONALITY OF CLASS, RACE, AND SEXUALITY

The Half Of It manages to exhibit the intersectionality of class, race and sexuality – something most popular movies fail to do, or struggle to even juggle one. Other recent popular LGBTQ+ films have only portrayed white, middle or upper class characters, such as Love, Simon, Call Me By Your Name, and Booksmart.

Ellie’s lower-class status is brought into the picture right away. We see this as other students drive to school while Ellie has to bike through a canyon, when she is at first planning on going to a cheaper college rather than a better one, and when her electricity bill is overdue in the beginning of the movie. However, the overdue electricity bill was also due to her father’s accent. After the lights flicker within their home, Ellie asks her father (in Mandarin) if he called about the electricity. Without looking at her, he responds

“They don’t understand my accent.”

(Wu 9:24)

While this seems to be a simple detail, it is much more than that; Ellie’s father has a hard time getting necessities because of his accent and language barrier. It spells out the struggles of immigrants in America, as well as racism in a way. Ellie later tells Munksy that even though her father has a PhD in engineering from China, her dad wasn’t able to get an engineering job; Ellie’s parents had moved to America when she was young so that her father could become an engineer, and his jumping off point was supposed to be the train station in Squahamish that they live at. From there, he hoped to be promoted as time went on. However, the language barrier proved to be too much in the way, and possibly racism as well.

While Ellie doesn’t struggle with language, she experiences plenty of racial injustices as well. From microaggressions of being called “The Chinese Girl,” as well as her awful nickname “Chugga Chugga Chu Chu,” her fellow classmates pick on her for being Chinese. One group of guys relentlessly tease her, and even sabotage her piano performance at the senior recital – and there seems to be no real reason besides the fact that she is different, or Chinese.

The film also obviously addresses her sexuality, and in a refreshing way. It isn’t about Ellie coming out, but her exploring her feelings, even if it’s through catfishing Aster in a sense. But it’s also about Ellie having to hide her sexuality in a religious town; as Munksy says so eloquently,

“…it would suck to have to pretend to be not you.. uh… your whole life.”

(Wu 1:27:52)

All three of these subjects weave a beautiful film together, and explore a dynamic not usually seen in others. The inclusion of diversity in race, class, sexual orientation, and gender all in one film is important, especially of teenagers, and should be done more often; we can’t choose to only represent things that we like, prefer, or make us happy. Doing that would overlook many of the voices and experiences that all films should include. After all, this is the United States, and we have a very diverse population here, as well as a large immigrant population, so the American film industry should start realizing that too. Having young people grow up seeing someone like them – whether they are a Chinese Immigrant, LGBTQ+, in a lower class, or in this case, all three – makes such an impact on someone’s life.

THE MALE GAZE

Another accomplishment that The Half Of It completes is the lack of the male gaze. In most Hollywood films, women are sexulized by the male gaze, and treated as objects of desire. In Film Feminisms: A Global Introduction, Kristin Lené Hole and Dijana Jelača describe how Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” identifies

“a dominant pattern in class Hollywood cinema within which women onscreen embody to-be-looked-at-ness, and are framed as objects of male desire.”

(Hole and Jelača 54)

They go on to say that “Mulvey argues that this gaze is a controlling device that perpetuates the patriarchal framing of women as sexual objects of male desire” (Hole and Jelača 54). Examples of this male gaze is when shots fixate on the woman’s body, or specific parts of it, such as her legs, and the sectionalization of the body, especially while undressed.

The Half Of It never exhibits the male gaze throughout the course of the film, and this is especially apparent with a scene with Ellie and Aster in a hot spring. Aster brings Ellie to a hot spring, and begins to undress; however, we only see the back of her, shoulders up, for a second as she takes off her shirt, then the frame goes to Ellie’s surprised reaction, who instantly turns around to respect Aster’s privacy. The camera turns to face Ellie looking at the trees, who awkwardly asks “Are these deciduous trees?” (Wu 1:08:24). The camera does not exert the male gaze on Aster in this scene, and continues to do so as Ellie gets into the spring. Ellie goes in with a shirt on, due to her shyness of course, and we never see anything below Aster’s collarbone while she’s in the water. Even when Aster gets out to turn on the radio, the gaze does not follow her body, nor show any of it, besides her hand turning on the radio. At one point, we see the both of them laying on their backs, however the frame is only focused on the side view of their heads, side-by-side as opposites. Even when this scene pulls out to a bird’s eye view, the girls are not conceived with a male gaze; Aster has also put on a shirt by this point, and it shows a moment of understanding silence for the two (and no, their shirts aren’t suction-cupped to their breasts as many other films do).

It is such a refreshing take on scenes like these where women – especially teenagers – are not sexualized and treated as objects of desire. This scene focuses on their conversation and their bond forming, not the fact that they are nude; instead, it provides a non-sexual intimacy of comfort for Ellie to experience with Aster. It subverses the male gaze and therefore the patriarchal power and framing of women as sexual objects of desire. Here, Aster and Ellie are women – and their own persons – who are coming to an understanding in this delicate, bonding moment.

The male gaze can be overpowering in many films, even with young women in them. By having women not be sexualized in every which way they can be, The Half Of It succeeds in letting these young girls just be these young girls. The Half Of It actively combats having to be sexy, or beautiful, but instead shows girls that they can just be themselves, and this is especially shown by Ellie wearing her shirt and Aster later changing into one. This alleviates the indirect pressure on girls and women of having to conform to these patriarchal ideas of having to be “desirable,” a stressor that women grow up with and learn not only from the real people around them, but what they watch or read or observe.

AUTHORSHIP

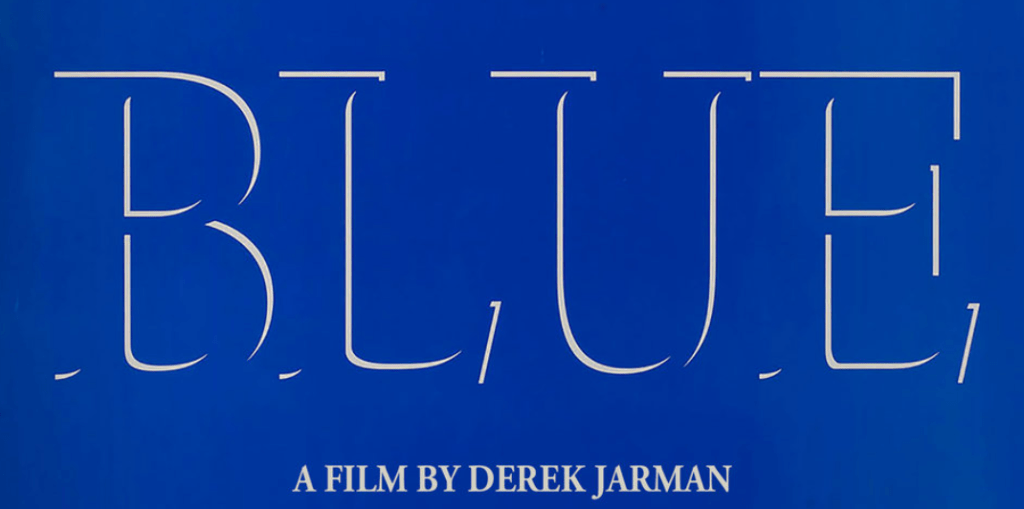

A big issue that the filmmaking industry has, and notably Hollywood, is authorship. Many have problems with writers and directors representing races or sexualities without sharing the same ones, as it can lead to misrepresentation as well as other issues with culture and identity. For example, Paris Is Burning, a documentary about the African American and Latinx ball/drag community in New York City, was directed by Jennie Livingston, a white lesbian cis-gender woman. Some had issues with her representing this group as it had seemed to impact how the group and culture itself was misrepresented in the documentary.

However, The Half Of It seems to have “appropriate” authorship. Director and screenwriter Alice Wu is a Chinese American who is lesbian, and in multiple interviews she has mentioned that much of the story was based off of her own experiences. So why is this so important? For starters, woman representation both on and off the screen is devastatingly low. In a study conducted by the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, 1,200 popular films from the years 2007 to 2018 were analyzed, showing that only 4.3% of directors were female. According to the same study, only nine of the 1,200 top grossing films released between 2007 and 2018 were directed by women of color, “with no noticeable change over time: five were directed by African American women, three by Asian women, and one by a Latina” (Obenson). In this study, LGBTQ+ directors weren’t even mentioned, which spells out an even bleaker image.

Alice Wu’s authorship not only boasts accuracy and relatability of the subjects included within the film, but inclusion in the film industry of race, gender and sexuality. This inclusion itself creates greater intersectional representation, and even creates someone who is not white and straight for others to look up to. Authorship directly impacts the story and every detail within a film; the showing of Chinese heritage, immigrant and class struggles, micro-aggressions and racism, as well as the portrayal of a LGBTQ+ character came from Wu herself. We need to hear and see more diverse voices in films, and that includes the directors and writers themselves.

ISSUES: CONSENT AND CHEATING

One issue that is indirectly addressed in this film is consent. After Munksy takes Aster on a second date – which didn’t end in a disaster like the first one thanks to Ellie – he kisses her. We don’t see this on screen, but in a different scene where he tells Ellie about their kiss while they shop for her senior recital outfit. This is followed by Ellie furrowing her eyebrows as she makes a confused face. This can be taken as her being upset about him and Aster kissing since she does like Aster, however it seems more of the sentiment of genuine confusion. She asks timidly how a kiss even happens. This is followed by an awkward dialogue sequence:

Munksy proceeds to shrug and says “I-I kissed her.”

“How do you know she wants to be kissed?” Ellie asks.

“Um… she gives you a look.”

“A look?”

“Yeah, like um -” Munksy then awkwardly proceeds to make “the look.” Ellie is left even more confused, and Munksy finally says

“Ok she just gives you a look, and when you see the look, you make your move, otherwise you come off looking like a real putz.”

(putz meaning stupid) (Wu 53:13-53:40)

I believe that Ellie’s confusion and skepticality is supposed to reflect the audience’s sentiment – we with Ellie Chu are asking if Aster really wanted to be kissed. Ellie’s reaction to Munsky’s poor explanation/reason for kissing Aster emphasizes the whole idea of consent, and that a “look” isn’t exactly enough for it. Munsky’s reasoning is even proven wrong later within the movie when he tries to kiss Ellie after his football game. Ellie abruptly pulls away and Munsky asks “Y-You don’t want me to kiss you?” and Ellie responds with a loud “No!” (Wu 1:19:40-1:19:45).

However, despite this being what I believed as a critique, at the end of the film we see Ellie kiss Aster without direct consent either. After Ellie says her final goodbyes to Aster before leaving for college, Ellie starts to walk away, then suddenly runs back to kiss Aster. I was very surprised and honestly a little disappointed. Although it felt like a great scene at the moment, upon further contemplation of consent it felt like a not-so-great moment. I think if Wu still wanted to include this kiss within the movie, it would have been very in-character for Ellie to ask Aster beforehand. Who knows, maybe Aster would say yes. Especially during the time of the “Me Too” movement, this is something that should be re-addressed within the film.

Another issue with the film is that Aster is cheating on her boyfriend Trig the whole time. When I first watched it I for some reason assumed that Trig and Aster were just an on and off thing, something that is very frequent in high school. However, when Aster tells Ellie at the pond that Trig intends to propose to her – and he eventually does in the church – it is pronounced as a more serious relationship. It’s not a very great message that the film portrays about cheating, and it definitely could have been avoided. Maybe Wu could have made Aster and Trig into an on and off couple, or maybe even had them break up for a bit when she is seeing Munksy and then get back together after Aster stops talking to him.

However, Trig doesn’t seem to be so loyal either. At the senior recital when Ellie plays her song on the guitar, he remarks “When did Ellie Chu get kind of hot?” (1:00:18). Also, later in the film, Trig approaches Ellie as she is coming home from Munsky’s football game, saying that he knows that she’s in love with him since she’s been following him around (but the audience knows that Ellie is actually following Aster who just happens to be with him). When Ellie sarcastically says yes, she is, Trig takes it seriously and tries to lean in for a kiss; Ellie’s dad then sprays him from the window of their home. Again, this is not a great portrayal of a high school relationship – or any relationship really – and sends out a questionable message about cheating.

CONCLUSION

Despite its flaws, The Half Of It is a movie that is very needed in today’s society and film industry. It portrays so many different aspects of life – from race, sexaulity, bullying, class, love, school, family – in a very relatable, refreshing, and informative way. Many people grow up through reading books and watching films and TV shows, and they have a role in people’s lives as many people learn from portrayals and stories within those works, whether the audience realizes this or not. Having a film about teenagers like The Half Of It allows the audience to learn so much more than from a usual Hollywood white-washed, perfect-ending love triangle. There is more representation and inclusion of different groups, and the film succeeds in sending important messages about sexuality, race, gender, and class by emphasizing things such as the micro-aggressions that Ellie experiences, and de-emphasizing others such as not sexualizing Aster and Ellie in the hot spring scene. This film is not perfect, but it doesn’t have to be; most films are never going to be perfect, but ones like The Half Of It are trying, and are doing better than most. And, we live and we learn, and move ahead trying to fix what isn’t perfect in the future. This is a film unlike many others, and that’s the unfortunate part – there should be more films like this, and hopefully more films and even TV shows in the future will follow in similar footsteps.

WORKS CITED

Dijana, Jelača and Hole Kristin Lené. “Chapter two: Spectatorship and Reception.” Film Feminisms: a Global Introduction, Routledge, 2019, p. 54.

Obenson, Tambay. “For Black Directors, 2018 Was a Banner Year, Not So Much for Women, Asians – Report.” IndieWire, Penske Business Media, 4 Jan. 2019, http://www.indiewire.com/2019/01/hollywood-diversity-inclusion-2018-black-directors-women-directors-1202031981/.

Smith, Stacy L, et al. Inequality in 1,200 Popular Films: Examining Portrayals of Gender, Race/Ethnicity, LGBTQ & Disability from 2007 to 2018. University of Southern California, 2019, http://assets.uscannenberg.org/docs/aii-inequality-report-2019-09-03.pdf.

Wu, Alice, director. The Half Of It. Likely Story and Netflix, 2020.